This note is a mental model for how Prometheus discovers and scrapes metrics in Kubernetes.

The lens I want to keep throughout is:

- Where will the scrape config file sit?

(Prometheus repo vs application repo) - In which namespace will the serviceMonitor sit?

(and how Prometheus finds it)

At a high level there are two ways to tell Prometheus about a /metrics endpoint:

- Static via in the Prometheus config file.

- Dynamic via (CRD from Prometheus Operator) with label‑based discovery.

Approach 1: Static scrape_config:

This is the traditional way: you manually configure a scrape job in prometheus.yaml.

The natural questions here are:

- How do I configure the

scrape_configjob? - Where will that config YAML file sit? (Prometheus repo or application repo?)

How question:

You define a scrape_configs job in the Prometheus config:

scrape_configs:

- job_name: 'otel-collector'

scrape_interval: 120s

static_configs:

- targets: ['otel-collector:9090']

metrics_path: '/metrics'Prometheus will then call: GET http://otel-collector:9090/metrics on configured interval.

An example in otel-contrib repo – here

Where question:

In this model the scrape config is centralized in the Prometheus deployment repo.

prometheus-deployment-repo/ #Platform team owns

├── prometheus.yaml # Main config with scrape_configs

├── prometheus-deployment.yaml

└── prometheus-configmap.yaml

otel-collector-repo/ # App team owns

├── deployment.yaml

├── service.yaml

└── otel-collector.yaml

# NO prometheus.yaml hereThis is a very manual contract between the application and the Prometheus and potentially has problems with Day1 and Day2 operations, as the application evolved.

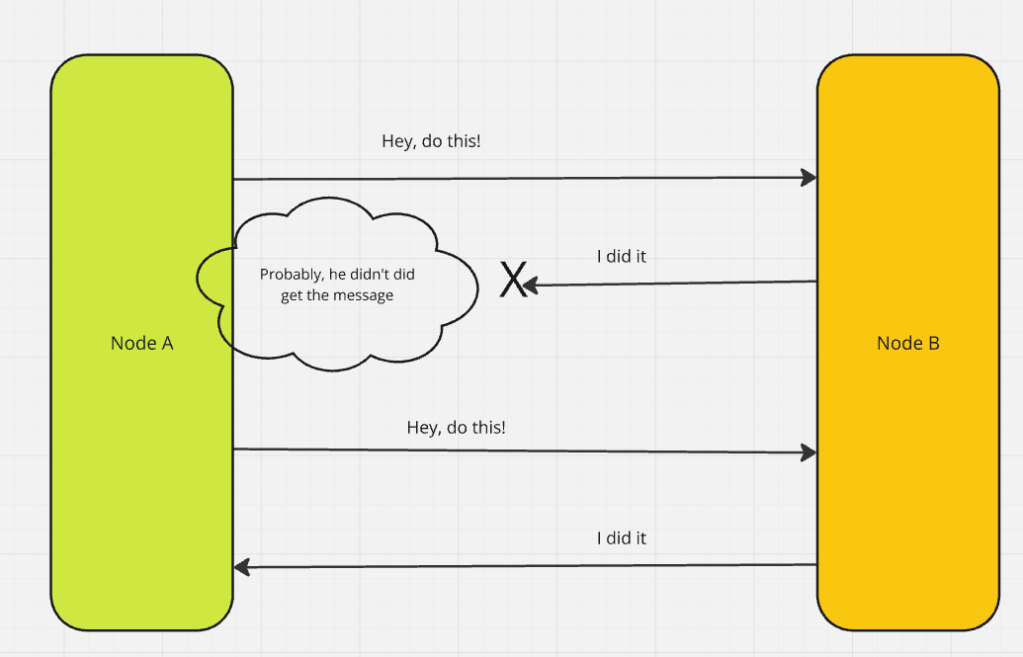

Everytime there is a change in applicationName or Port, the same changes will have to put on the Prometheus repo as well. Failure of which will lead into scrape failures.

Approach 2: Dynamic scraping with ServiceMonitor

Rather than manual, there is also an option of Dynamic discovery of a new endpoint on EKS that prometheus can figure out it has to scraped.

This is done via ServiceMonitor which is a CRD from Prometheus-operator. Details here

Once serviceMonitor CRD is present in the cluster, the Prometheus-operator then:

- Watches

ServiceMonitorresources in the EKS cluster. - Translates them into Prometheus scrape configs.

- Updates the Prometheus server configuration automatically.

Note that, if ServiceMonitor CRD is present, other tools can just set the variabletruefor serviceMonitor in their helm charts and start getting scraped by prometheus.

Looking through serviceMonitor from the lens of :

– How to configure serviceMonitor for my app ?

– Where (which namespace) should I push my serviceMonitor to ?

How question:

Configure a kind: ServiceMonitor kubernetes resource in the application repo. Example of the same below.

apiVersion: monitoring.coreos.com/v1

kind: ServiceMonitor

metadata:

name: otel-collector

namespace: otel-demo

labels:

prometheus: fabric # Must match Prometheus selector

spec:

selector:

matchLabels:

app: otel-collector # Selects Services with this label

namespaceSelector:

matchNames:

- otel-demo

endpoints:

- port: metrics # Port NAME (not number!)

interval: 120s

So the “How“ for dynamic scraping is: “Define a ServiceMonitor next to your Deployment and Service in your app repo.”

Where question:

With static scrape_config, the “where” question was: which repo owns the config file?With ServiceMonitor, the YAML lives in the app repo, so the “where” question shifts to:

In which Kubernetes namespace should I deploy the serviceMonitor so that Prometheus discovers it?

This is controlled by the serviceMonitorNamespaceSelector field in the Prometheus CRD.

apiVersion: monitoring.coreos.com/v1

kind: Prometheus

metadata:

name: platform-prometheus

namespace: prometheus-platform

spec:

serviceMonitorSelector:

matchLabels:

prometheus: platform # only watch SMs with this label

serviceMonitorNamespaceSelector: {}Prometheus can be setup in 3 different ways to do this:

(1) Watch service monitor in all Namespaces.

Prometheus Operator watches every namespace for ServiceMonitors with label prometheus: fabric in below example.

apiVersion: monitoring.coreos.com/v1

kind: Prometheus

metadata:

name: fabric-prometheus

namespace: prometheus-fabric

spec:

serviceMonitorSelector:

matchLabels:

prometheus: fabric

serviceMonitorNamespaceSelector:

{} # Empty = all namespaces(2) Watch only specific Namespaces

Only ServiceMonitors in namespaces labeled monitoring: enabled are picked up in below example.

apiVersion: monitoring.coreos.com/v1

kind: Prometheus

metadata:

name: fabric-prometheus

namespace: prometheus-fabric

spec:

serviceMonitorSelector:

matchLabels:

prometheus: fabric

serviceMonitorNamespaceSelector:

matchLabels:

monitoring: enabled # Only namespaces with this label(3) Watch only Prometheus Namespace.

ServiceMonitors must be in prometheus-fabric namespace (centralized model) in below example

apiVersion: monitoring.coreos.com/v1

kind: Prometheus

metadata:

name: fabric-prometheus

namespace: prometheus-fabric

spec:

serviceMonitorSelector:

matchLabels:

prometheus: fabric

serviceMonitorNamespaceSelector:

matchNames:

- prometheus-fabric # Only this namespaceBelow is the workflow of Dynamic, label-based Discovery of a scrape endpoint:

In below workflow example, prometheus is deployed in prometheus-namespace and the application is deployed in otel-demo.

The workflow shows tying up between :

Promethues –> ServiceMonitor –> Service –> Pods

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ 1. Prometheus (namespace: prometheus-namespace) │

│ │

│ serviceMonitorSelector: │

│ matchLabels: │

│ prometheus: fabric ◄────────────────────┐ │

│ │ │

│ serviceMonitorNamespaceSelector: {} │ │

│ (empty = watch all namespaces) │ │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────────┼──────────┘

│

┌──────────────────────────────┘

│ Operator watches all namespaces

▼

┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ 2. ServiceMonitor (namespace: otel-demo) │

│ │

│ metadata: │

│ labels: │

│ prometheus: fabric ◄─────────────────┐ │

│ spec: │ │

│ selector: │ │

│ matchLabels: │ │

│ app: otel-collector ◄──────────┐ │ │

└───────────────────────────────────────────┼───┼────────────┘

│ │

┌───────────────────────┘ │

│ Selects Services │

▼ │

┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ 3. Service (namespace: otel-demo) │

│ │

│ metadata: │

│ labels: │

│ app: otel-collector ◄────────────────┐ │

│ spec: │ │

│ selector: │ │

│ app: otel-collector ◄────────────┐ │ │

│ ports: │ │ │

│ - name: metrics ◄────────────┐ │ │ │

│ port: 9090 │ │ │ │

└──────────────────────────────────────┼───┼───┼─────────────┘

│ │ │

┌──────────────────┘ │ │

│ Port name match │ │

│ │ │

│ ┌───────────────────┘ │

│ │ Selects Pods │

▼ ▼ │

┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ 4. Pod (namespace: otel-demo) │

│ │

│ metadata: │

│ labels: │

│ app: otel-collector ◄────────────────┐ │

│ spec: │ │

│ containers: │ │

│ - ports: │ │

│ - name: metrics │ │

│ containerPort: 9090 ◄──────────┼─────────────┤

└──────────────────────────────────────────────┼─────────────┘

│

┌──────────────────────────┘

│ Prometheus scrapes

▼

GET http://10.0.1.50:9090/metrics