When studying Chapter 4 of Designing Data-Intensive Applications (Encoding and Evolution), I quickly encounters a level of granularity that seems mechanical: binary formats, schema evolution, and serialization techniques. Yet behind this technical scaffolding lies something conceptually deeper. Encoding is not merely a process of serialization; it is the very grammar through which distributed systems express and interpret meaning. It is the act that allows a system’s internal thoughts — the data in memory — to be externalized into a communicable form. Without it, a database, an API, or a Kafka stream would be nothing but incomprehensible noise.

But, Why should engineers care about encoding? In distributed systems, encoding preserves meaning as information crosses process boundaries. It ensures independent systems communicate coherently. Poor encoding causes brittle integrations, incompatibilities, and data corruption. Engineers who grasp encoding design for interoperability, evolution, and longevity.

This writeup reframes encoding as a semantic bridge between systems by overlaying it with two mental models: the Dataflow Model, which describes how data traverses through software, and the OSI Model, which explains how those flows are layered and transmitted across networks. When examined together, these frameworks reveal encoding as the connective tissue that binds computation, communication, and storage.

- So, What is Encoding ?

- The Dataflow Model: Where Encoding Occurs

- The OSI Model: Layers of Translation

- Example : Workflow

- Mental Models:

- Other Artifacts:

So, What is Encoding ?

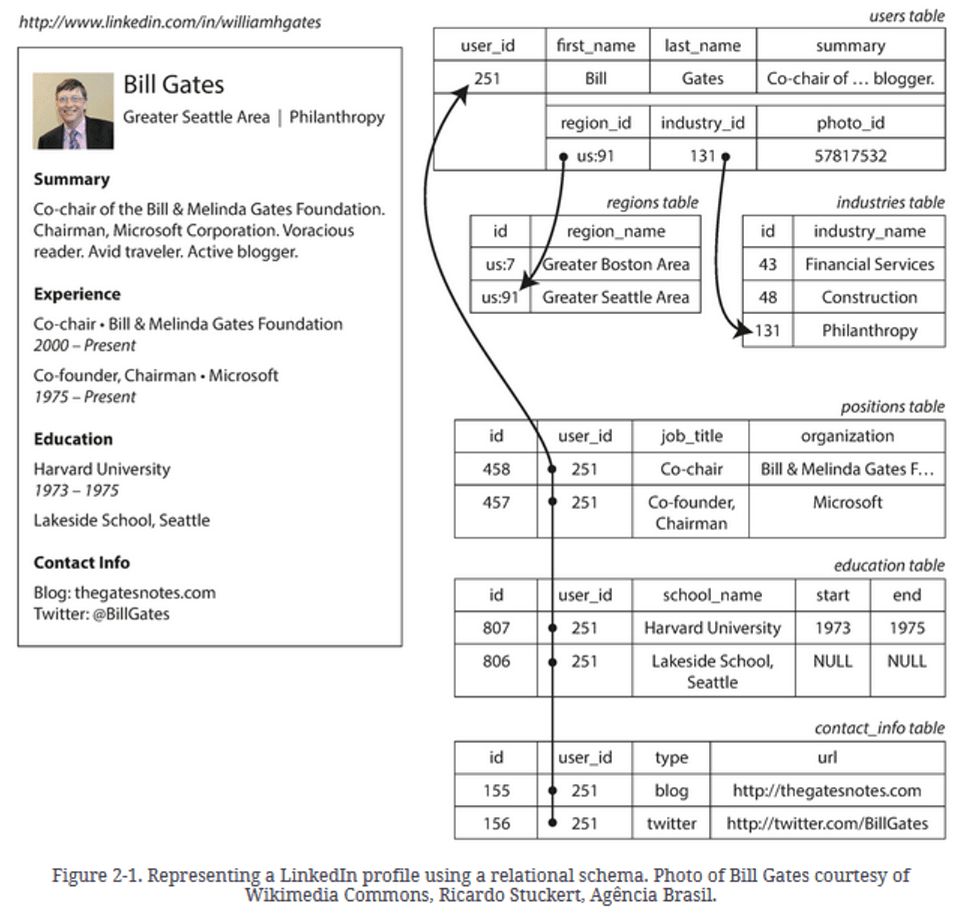

All computation deals with data in two representations: the in-memory form, which is rich with pointers, structures, and types meaningful only within a program’s runtime, and the external form (stored on disk / sent over network), which reduces those abstractions into bytes. The act of transforming one into the other is encoding; its inverse, decoding, restores those bytes into something the program can reason about again.

This translation is omnipresent. A database write, an HTTP call, a message on a stream — all are expressions of the same principle: in-memory meaning must be serialized before it can cross a boundary. These boundaries define the seams of distributed systems, and it is at those seams where encoding performs its essential work.

Some of the general encoding formats that are used across programming languages are JSON, XML and the Binary variants of them (BSON, Avro, Thrift, MessagePack etc).

– When an application sends data to DB, the encoded format is generally a Binary Variant (BSON in mongo)

– When service 1 sends data to service2 via an api payload, the data could be encoded as JSON within the request body.

The Dataflow Model: Where Encoding Occurs

From the perspective of a dataflow, encoding appears at every point where one process hands information to another. In modern systems, these flows take three canonical forms:

- Application to Database – An application writes structured data into a persistent store. The database driver encodes in-memory objects into a format the database can understand — BSON for MongoDB, Avro for columnar systems, or binary for relational storage.

- Application to Application (REST or RPC) – One service communicates with another, encoding its data as JSON or Protobuf over HTTP. The receiver decodes the request body into a native object model.

- Application via Message Bus (Kafka or Pub/Sub) – A producer emits a serialized message, often governed by a schema registry, which ensures that consumers can decode it reliably.

In all these flows, encoding happens at the application boundary. Everything beneath — the network stack, the transport layer, even encryption — concerns itself only with delivery, not meaning. As DDIA succinctly puts it: “Meaningful encoding happens at Layer 7.”

With those above details, lets expand a little in detail about two Dataflow paths and see how Encoding happens.

(1) Application to Database

(2) Application to Application

Application to Database Communication:

In the case of application-to-database communication, encoding operates as a translator between the in-memory world of the application and the on-disk structures of the database. When an application issues a write, it first transforms its in-memory representation of data into a database-friendly format through the database driver. The driver is the actual component that handles the encoding process. For instance, when a Python or Java program writes to MongoDB, the driver converts objects into BSON—a binary representation of JSON—before transmitting it over the network to the MongoDB server. When the database returns data, the driver reverses the process by decoding BSON back into language-native objects. This process ensures that the semantics of the data remain consistent even as it moves between memory, wire, and storage.

Encoding at this layer, though often hidden from us, is critical for maintaining schema compatibility between the application’s data model and the database schema. It allows databases to be agnostic of programming language details while providing efficient on-disk representation. Each read or write is therefore an act of translation: from structured programmatic state to persistent binary form, and back.

Application to Application Communication:

When two applications exchange data, encoding ensures that both sides share a consistent understanding of structure and semantics. In HTTP-based systems, Service A (client) serializes data into JSON and sends it as the body of a POST or PUT request. The server (Service B) decodes this payload back into an internal data structure for processing. The HTTP protocol itself is merely the courier—the JSON payload is the encoded meaning riding inside the request. This pattern promotes interoperability because nearly every platform can parse JSON.

- S1 serializes payload → JSON text (this is the endcoding part)

- HTTP sends that text as the body request (this is imp part which I missed earlier)

- S2’s HTTP server framework reads it and parses it into native objects

In contrast, systems employing gRPC communicate using Protocol Buffers, a binary schema-based format. gRPC compiles the shared .proto file into stubs for both client and server, ensuring a strong contract between them. When Service A invokes a method defined in this schema, the gRPC library encodes the message into a compact binary stream, transmits it via HTTP/2, and Service B decodes it according to the same schema. The encoding format—textual JSON for REST or binary Protobuf for gRPC—defines not only the data structure but also the performance characteristics and coupling between services.

The OSI Model: Layers of Translation

If you note in the details of above section, most of the encoding we discuss is at Layer7 (application layer). Hence the protocols that we talk about are all L7 protocols – HTTP, gRPC etc.

With that point as note, I tried to overlay the mental model of OSI Networking model on top of Encoding model, to understand better and stitch them together.

While most of the translation of data during encoding happens at L7, other layers with in OSI model also do their own form of encoding. Each layer wraps the one above it like a nested envelope, performing its own encoding and decoding. But while Layers 1–6 ensure reliable delivery, only Layer 7 encodes meaning. A JSON document or a Protobuf message exists entirely at this level, where software systems express intent and structure.

Layer 7 Application → HTTP + JSON / gRPC + Protobuf

Layer 6 Presentation → TLS encryption, UTF‑8 conversion

Layer 5 Session → Connection management

Layer 4 Transport → TCP segmentation, reliability

Layer 3 Network → IP addressing, routing

Layer 2 Data Link → Frame delivery, MAC addressing

Layer 1 Physical → Bits on wire, voltage, lightExample : Workflow

With above details, lets try a usecase of encoding between two services, which are taking to each other in a restful way via apis. (s1 and s2)

Lets plot the flow diagram of encoding with OSI model on top of it

Mental Models:

To conclude, below are the mental models to think through, when considering Encoding:

- Different dataflow patterns (

app--> DB,app--> app,app --> kafka --> app) - Encoding at different OSI layers (L7 all the way till L1)

Other Artifacts:

- All the referenced papers and material from DDIA – https://github.com/ept/ddia-references/blob/master/chapter-04-refs.md

- Roy Fielding publication on what is considered a RESTFUL service – https://ics.uci.edu/~fielding/pubs/dissertation/fielding_dissertation.pdf

- DDIA book – https://dataintensive.net/